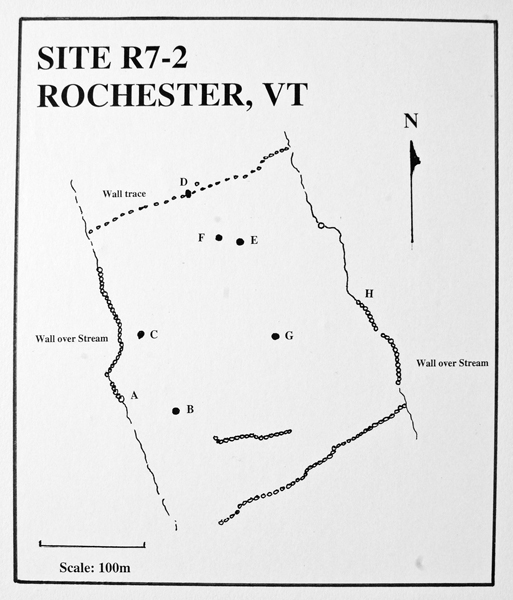

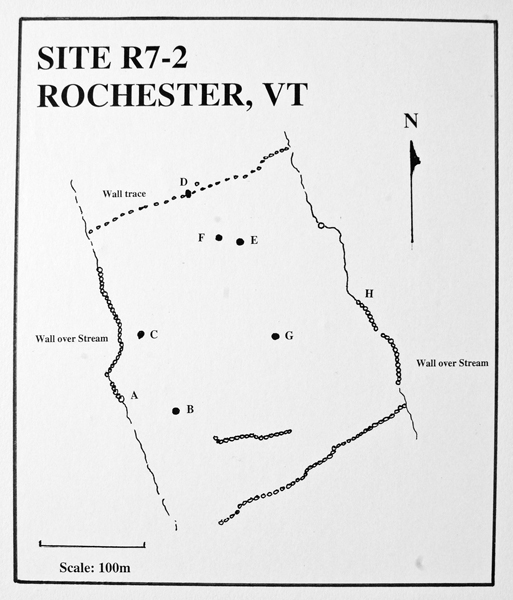

Fig 1

Within a mile and a half of the Smith cairn site off West Hill Road, which is the largest cairn site in the area with more than 150 manmade stone constructions of various shapes and sizes, are three other cairn sites, each designated with a letter and a numeral. The Smith site is often referred to as R7-1. Site R7-2, for instance, which is the subject of this report, is approximately1.3 miles south of the Smith site. R7-6 is on the other side of Jones Mountain off Bingo Road, one mile away; and R7-8, next to a beaver pond, is .7 miles northeast of the Smith site. None of these is as large as the Smith site in terms of the number and variety of the stonework or even the size of the area, but each is distinctive and important in its own right, and all display the same fastidious stonework that one finds at the Smith site. This quality of workmanship, which if one thinks about it, raises the awkward question of who built all these structures, and when. A few years ago, some half-dozen archaeologists met at the Smith site one spring day, and because they saw only this one site, they were under the mistaken impression that one of the farmers who owned the property was responsible for all the stonework. Little did they know that similar well-built cairns were not only within a mile or two of this one, but also at dispersed sites in Vermont and elsewhere (see Stockbridge Cairn Site), implying that the construction of these mysterious structures was part of a widespread cultural activity not related to colonial farming.

Site R7-2 is perhaps the most enticing, perplexing and fascinating of all the sites mentioned above. Located off West Hill Road, it is roughly square in area, approximately 10.3 acres in size, and bordered by two streams running north-south, each about 200 m (670 ft.) apart, and by two walls running east-west, as shown in Figure 1, again the approximate distance apart. All the stone features are contained within these borders. Five years ago, Ernie Clifford, a perceptive Vermont native and intrepid investigator of Vermont stonework, showed me this and other cairn sites in the Rochester area. He, more than anyone, is responsible for bringing these important sites to my and other's attention, and he has conducted important research into this particular site.

Fig 1

By far, the wall-over-the-stream at point A on Figure 1 is the most intriguing and impressive of all the features at the site. At its southern end it is an awesome sight, being an imposing 2 m (7 ft.) and 1.8 m (6 ft.) wide (Fig. 2), gradually tapering to a still tall but more modest .9 m (3 ft) to 1.5 meters (5 ft.) for the next 30 meters (100 ft.). Some of the stones comprising the bottom end of the wall are massive, such as a 1.2 m (4 ft.) long horizontal slab of stone, which based on size alone, must weigh more than 450 kg. (1000 lbs). From here, the wall extends over 120 m (400 ft.) uphill to within about 6 m (20 ft.) south of the wall trace at its northern border. The wall does not cross or parallel the stream but is constructed directly on top of it, meaning that it follows all the perambulations of the stream as it meanders down the slope from the north. One can sense the curvature of the wall near the very bottom, by standing on top and looking south to where the wall begins (Fig. 3). The nearly 46 m (150 ft.) long southern portion of the wall is the best preserved, and for the next 27 m (90 ft. or so uphill the wall deteriorates to a jumble of massive loose stones with five separate breaks or breeches in it.

In October 2002, Ernie paced off the wall from its northern end, recording each of the five wall breaks and other distinctive features as he encountered them down to the bottom, or the wall's beginning. Years earlier he had noticed that there were large capstones at the various breaks in the wall, and that there appeared to be a culvert underneath these stones. He then noted that this culvert seemed to begin at least 7.6 m (25 ft.) in front of the bottom part of the wall, just to the right of the base of the large tree in the bottom center of Figure 4. Figure 5 is a detail of the opening, which shows the piled support stones on the left, and some support stones on the right which are somewhat out of place; above is the capstone.

The wall was intentionally breeched at four locations, undoubtedly to allow the farmer who owned property west of the wall to have access to his orchard on the east side of it. The stones that were part of the wall at these points were probably used to construct the foundations of the barn and house plus the walls that are found in the vicinity of the farmhouse. At the four breeched spots large flat capstones are exposed. Ernie found that for most of the capstones, their widths average about 1 meter (3 feet), while the lengths vary from 1.5 m (5 ft.) to 2.4 m (8 ft.), their long axis being perpendicular to the channel that they cover. Having wandered extensively through the area, I have seen rounded and some smallish flat pieces of gneiss and other types of rock, but not large flat slabs. I've often wondered where all these capstones came from. There must be more than a hundred of them along the length of this wall, and not having seen any stones this size or shape in the area covered by R7-2, I am convinced that they must have come from somewhere else and then were carried to the wall-over-the-stream site to be used to cover the culvert. This must have been a major undertaking, and the labor involved must have been extensive, undoubtedly comprising the effort of many people. At about 250 feet from the bottom of the wall is one of the areas where several capstones are exposed. Ernie Clifford is shown at this location (Fig. 6) peering with the aid of a small flashlight into one of the cracks between the capstones. Another view of this location (Fig. 7) shows the opening to the culvert, behind and above which is the rough wall sinuously curving up the slope, and Figure 8 is a detail of the culvert opening. In an e-mail Ernie sent to me five years ago, he described the culvert channel at this location as being .6 m (2 ft.) wide and .6 meters deep below the capstones. Where the walls could be observed, they consisted of several courses of flat stones, the one exception being a very large stone 1.5 m (5 ft.) long and .4 m (18 in.) high.